Sunday April 11th Mr Whitman of E Bridgewater preached

He gave us two good sermons but he is very dull and

I was very sleepy. Came home at noon Alson & wife

came to Augustus’ After meeting went into Edwins

Augustus & E Andrews came there. Susan staid

at home from everything It has been very pleasant

In the tradition of their Puritan ancestors, Evelina and her family did not celebrate Easter. No hidden eggs or little bunnies or even new bonnets appeared in the Unitarian homes of Easton on Easter Sunday, 1852. Many of the Catholic families in town, however, would have celebrated this significant Christian holiday, further underscoring the strong cultural differences between the new Irish and the old Yankees of Massachusetts.

Other parts of the country celebrated this holiest of Christian remembrances. It was the German community of the mid-Atlantic states, better known as the Pennsylvania Dutch who, some say, introduced the Easter bunny to America in the 1700s. The rabbit and the egg were symbols of the Germanic fertility goddess Eostre, whose pagan festival was eventually taken over by early Christians as a celebration of Christ’s death and resurrection.

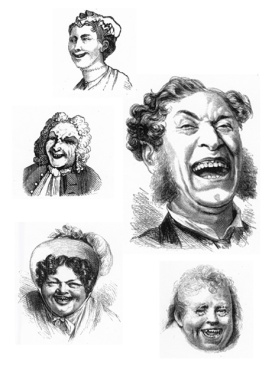

It being Sunday, the Ameses went to meeting, at least, for both an afternoon and a morning service. Reverend Whitwell, the usual minister, was replaced today by Mr. Whitman from East Bridgewater who was, unfortunately, “very dull.” Evelina struggled to stay awake.